Architecture and Interior Design

These two go hand-in-hand: you cannot have an interior without an exterior,

and an exterior without an interior is just a façade without a real use. Many of the best

architects were also great interior designers.

Though I am greatly interested in two general time periods,

medieval and late nineteenth/early twentieth century, it is difficult to address the Middle Ages

in terms of ‘architects’ and ‘designers’, partly because such official labels

were not used, but largely because the practitioners are lost to us.

We do in fact have the names of a surprisingly large number of medieval English architects

(see English Medieval Architects: A Biographical Dictionary down to 1550

(2nd edn, 1984) by John Harvey), but we usually know little to nothing about them or their work.

So it must be sufficient to note that there are many medieval buildings which are both

beautiful and well-suited to their varied uses. The mere fact that they have survived for several centuries is testament to their qualities.

Similary, the creators of surviving wonders such as the Book of Kells,

the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreau (the rare attributable work, by Jean Pucelle), the Luttrell Psalter, Anglo-Saxon jewelry, etc.,

though by-and-large anonymous, clearly reveal the fact that exquisite beauty

played at least as great a part in medieval lives as it does in our own.

The sandstone flying buttresses of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Time for schools

Perhaps it is easier to discuss architecture in terms of ‘schools’ of

like-minded individuals. It is possible to go overboard in defining such groups, especially where

they did not self-define, or the category is very broad, but the period from roughly 1860 to 1925

saw the rise of several collections of people with shared ideas (dates are very approximate);

the gray items are of less interest to me (not because they aren’t good, but I have to draw the line somewhere):

- Arts and Crafts Movement (1860–1930)

- American Arts and Crafts Movement (1895–1920)

- Aesthetic Movement (1870–1900)

- Art Nouveau (1885–World War I)

- Vienna Secession (1897–World War I)

- School of Nancy (1900–World War I)—some building photos are here

- Wiener Werkstätte (1903–1932)

- Deutscher Werkbund (1907–1938)

- Art Deco (1905–1940)

- Bauhaus (1919–1933)

As you can see, the first World War was immensely destructive to the arts.

The second one didn’t help, either.

Architecture

Of all the arts, architecture is perhaps the most frustrating.

Despite the frequent exhortations of newspaper and magazine writers for the public to

‘join the debate’ surrounding a new building, the public usually has no input

at all into its design or use; even when asked for comments, such input is usually just redirected to /dev/null. (Sorry, computer joke.)

Architecture cannot be ignored—if you do not wish to see the exhibits of the Tate Modern, don’t

go inside, but you cannot very well avoid seeing the Tate Modern itself (which, for me, is far

more interesting than the contents) if you are anywhere near it.

Japan, which is known for its aesthetic sensibilities,

has some of the ugliest cityscapes I’ve seen—do zoning laws even exist in Japan?

Cities are ever-changing entities, so even the worst eyesores will eventually disappear,

but in the meantime one wonders if perhaps there shouldn’t be a more difficult test to pass

when seeking to become an architect.

Several city tourist boards publish very useful walking guides to Art Nouveau buildings (perhaps my favourite style

for architecture), including Paris, Brussels, Nancy and Prague.

Some of my favourite architects:

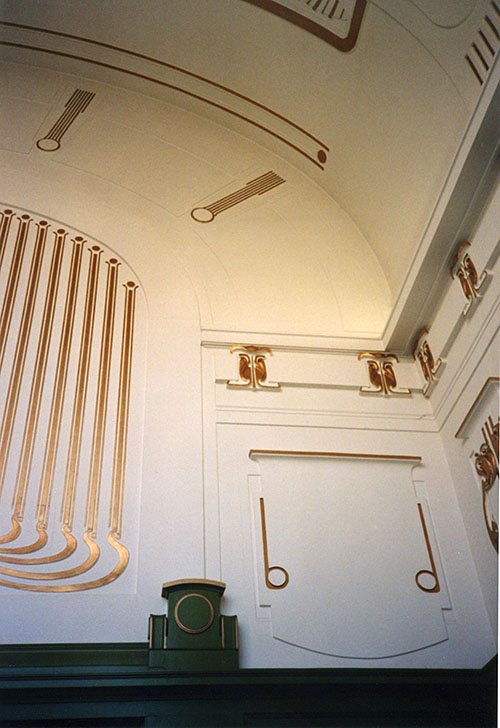

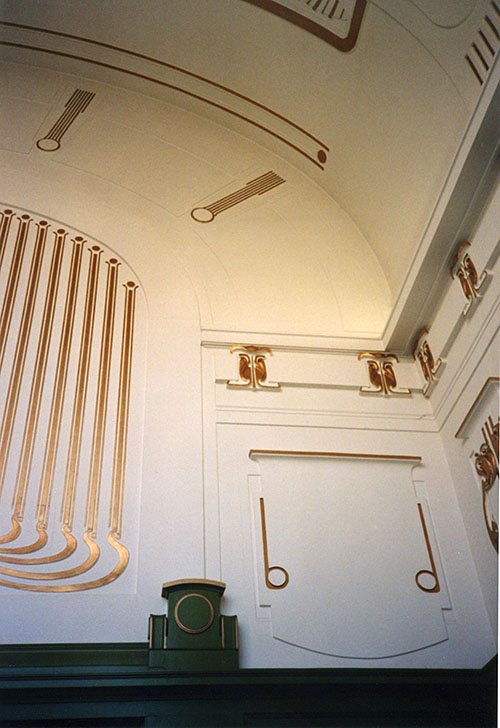

- Otto Wagner (1841–1918)

- An Austrian, working mostly in Vienna, Wagner was an important educator and a member of the Vienna Secession group.

No longer following the historical models slavishly, architects of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century quickly

developed many outstanding buildings, and Wagner is one of the best. He was also highly interested in urban planning,

and although most of his more grandiose ideas were thwarted by the fuddy-duddies in control, his drawings and writings still

have the power to surprise and please.

http://www.ottowagner.com/ow-werk/index.html

http://www.mak.at/e/jetzt/f_jetzt.htm

Interior of Wagner’s Karlsplatz station.

Exterior of Wagner’s Karlsplatz station.

- Greene & Greene (Charles, 1868–1957 and Henry, 1870–1954)

- These American architects, brothers, produced most of their work in Pasadena, California, where

some of their best homes still survive—Gamble House, Thorsen House and Blacker House all have

their own entries in Wikipedia. Important members of the American arts and crafts movement, they

were proponents of ‘whole-house’ architecture, where the interiors are just as important as

the exterior in forming a living space. Especially noteworthy is their extravagant use of exposed woodwork.

- Hector Guimard (1867–1942)

- French (as distinct from the Belgian) Art Nouveau architect and designer, his reputation has suffered due to the tragic destruction of

much of his work (including all but one – Porte Dauphine – of the famous Métro station major entrances).

What survives is largely in Paris, and by themselves make a trip to that city worthwhile.

(There are, of course, other reasons as well.)

- Victor Horta (1861–1947)

- The outstanding example of Belgian art nouveau designers, Horta is also important in the

development of later styles, eventually abandoning the organic nouveau look for such modernisms as

reinforced concrete and so-called ‘rational floor plans’. Although some of his work

has been destroyed, much still survives, particularly in Brussels.

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) and

Margaret MacDonald (1865–1933)

- You didn’t really think I would leave them off, did you?!

One of Glasgow’s best-known sons, Mackintosh was an architect,

designer, watercolourist and sculptor; his marriage to Margaret created a

design wonder. Their influence was strong in the Vienna Secession

(and Mackintosh, like Wagner, had numerous designs go unbuilt).

Hill House, Helensburgh (just north of Glasgow) has one of the finest interiors

in the world, a unified whole which must be seen in person to gain the entire fabulous effect.

(Externally, Hill House is only so-so.) We like Glasgow rather more than Edinburgh,

and this is one of the reasons why.

- Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956)

- Co-founder of the Vienna Secession, this Austrian architect and designer

(born in what is now the Czech Republic) has been the victim of much destruction and modification

of his buildings; they are still worth seeking out, though, with most in and around Vienna, and

the superb (though privately-owned) Palais Stoclet in Brussels. His extremely long design life covers

a huge variety of styles, and many of his designs are still sold – and still look up-to-date.

Interior Design

All of the above were also superb designers, fascinated by the ‘whole house’ concept,

controlling most aspects of their client’s home, sometimes down to doorknobs and bathroom fixtures. There are

also some wonderful designers who were not so active in architecture per se

(or did they just not get the opportunity?):

- Koloman Moser (1868–1918)

- Another member of the Vienna Secession, Moser manages to be of that style while somehow maintaining his own

fabulous look. Moser worked in virtually every area of design: books and graphic works, fashion,

stained glass, ceramics, glass, tableware, jewelry, furniture. A member of the Vienna Secession since

its beginning in 1897, Moser also founded (with Josef Hoffmann) the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, and

helped start the Austrian Werkbund in 1912.

- Edward William Godwin (1833–1886)

- Although also an architect, Godwin is known today almost entirely for his design.

An important figure in the development of the ‘Anglo-Japanese’ style, he began with an

interest in the much heavier (even clunky) neo-gothic design common in the 1850s and 60s

(e.g. William Burges), before moving on to the spidery furniture he is so famous for today.

- Christopher Dresser (1834–1904)

- This Scottish botanist and designer was one of the first westerners to visit Japan (1876–7)

and played an important part in the development of the ‘Anglo-Japanese’ Aesthetic style.

His metalwork (tea and coffee sets, etc.) are still astonishingly modern in feel. A true genius.

There are many others who could go on this list – Silver Studio, Beggarstaffs, several

Italian and Eastern European designers – and it is well worth your time to explore this period.

Anyone paying attention will notice the almost total lack of women on this list. Women were certainly

much involved, although frequently in less-publicised areas such as textile design. A case in point is

the recent book A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany girls,

New-York Historical Society, 2007. That a workshop as famous as Tiffany could hide the truth of

its famous lampshades is both a statement on the chauvinism of business-men, and a hint as to

just how widespread the un-acknowledged efforts of talented women were.

Suggested reading

There are lots of excellent books on these periods of architecture, art and design.

Below are some of my favourites:

- General—William Hardy, Steven Adams and Arie van de Lemme,

The Encyclopedia of Decorative Styles 1850–1935, New Burlington Books, 1988.

An older book, but very well-produced, with hundreds of illustrations, mostly in colour.

In three main sections: Arts & Crafts Movement; Art Nouveau; Art Deco. (Out of print.)

- General—Philippe Garner (ed.),

The Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts 1890–1940, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1978.

An even older book, but again well-produced, with hundreds of illustrations, about half in colour.

Very good on historical influences, with individual chapters by numerous authors. (Out of print.)

- Arts & Crafts—Peter Davey, Arts and Crafts Architecture,

Phaidon Press, 1995. Covers both the British and American movements, with lots of modern and contemporaneous

photos and other illustrations.

- Wiener Werkstätte—Werner J. Schweiger,

Wiener Werkstätte: Design in Vienna 1903–1932, Thames and Hudson, 1990.

A well-done English translation from the German edition, with many b&w illustrations and a few

colour plates, this is a history of a complex and volatile organisation.

- Wiener Werkstätte—Angela Völker,

Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte 1910–1932, Rizzoli, 1994. Concentrating on one of

the glories of the WW, textiles, this book has almost 400 illustrations (mostly in colour).

- Moser—Sandra Tretter (ed.), Koloman Moser 1868–1918, Leopold Museum/Prestel Verlag, 2007.

A collection of essays by various authors.

Superb, comprehensive volume (the catalog for a major exhibition on Moser),

this 450-page book finally gives Moser the kind of publication he so richly deserves.

- Moser—Maria Rennhofer, Koloman Moser: Master of Viennese Modernism, Thames and Hudson, 2002.

Translated by David Wilson. ‘375 illustrations, over 250 in colour’. Another excellent publication, also extremely well-produced.

After so many years of being just a chapter or less in general architecture books, it is wonderful that two such books focusing on Moser are available.

- Hoffmann—Christian Witt-Dörring (ed.), Hoffmann: Interiors 1902–1913,

Prestel Publishing, 2006. The catalog of a major exibition on Hoffmann, held at the

Neue Galerie in New York, this is a photo-rich guide to his concepts of room design. Good text as well,

by several authors.

- Hoffmann—Peter Noever (ed.), Josef Hoffmann Designs, Prestel

Publishing, 1992. From a major exhibition at the MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied Arts) in Vienna,

this excellent book covers all types of Hoffmann’s design work, with chapters by several authors.

Hundreds of illustrations, and still in print despite its age.

- American Arts & Crafts—Leslie Greene Bowman, American Arts & Crafts: Virtue in Design.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art in association with Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown and Company, 1990. The catalog of a travelling exhibition comprised largely of items from the Palevsky collection within the LA County museum, this book features short biographies and examples of works from a large number of names famous and not-so famous, with 190 color and 275 b&w illustrations. A good historical introduction to the American version of Arts & Crafts.

- American Arts & Crafts—Diane Chalmers Johnson, American Art Nouveau. Harry N. Abrams, 1979.

A fine reminder of the ‘good old days’ of tipped-in plates, the extensive text of this book may occasionally be out of date,

but worth reading nevertheless.

- Aesthetic movement—Lionel Lambourne, The Aesthetic movement, Phaidon Press, 1996.

An excellent survey of all aspects of the movement, and its influence on the continent.

- Dresser—Widar Halén, Christopher Dresser: A pioneer of modern design,

Phaidon, 1993. With 232 illustrations and a very good text. An excellent introduction to the

modernity of Dresser.

- Dresser—Stuart Durant, Christopher Dresser, Academy Editions, 1993.

A slightly larger-format book, again with over two hundred illustrations, and a chronological section

focusing on his life and works. Stunning cover, to boot. Both of these are still in print, and there

are other excellent, more recent, books by Whiteway or Lyons as well.

- Dresser—several of Dresser’s own writings are available,

including Traditional Arts and Crafts of Japan, the Dover Publications edition (1994) of

Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures, 1882 (this edition appears to be

out of print [a Dover book going OP ?!], but there are other facsimiles available from Nabu Press

and Braithwaite Press); Principles of Victorian Decorative Design, 1873,

Dover edition 1995 (the original did not have the word ‘Victorian’ in the title, of course);

and Studies in Design, 1876, published in large format by Studio Editions, London, 1988

(this may be OP, but there is another edition published by Gibbs Smith, 2002).

- Godwin—Susan Weber Soros, The Secular Furniture of E. W. Godwin,

Yale University Press, 1999. Seeks to include everything in Godwin’s enormous output

(there are 508 items in the catalogue raisonné). Includes a facsimile of the difficult-to-find

Art Furniture Catalogue of William Watt, 1877. Soros is also the editor of

E. W. Godwin: Aesthetic movement architect and designer, Yale University Press, 1999.

TOP