One of our favourite movies is William Wyler’s 1966 film How to Steal a Million, starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter O’Toole, Eli Wallach, Hugh Griffith—and Paris. As with fans of Amélie, there are now several websites with sections about this film: Parisian fields; Movie-tourist; Blond at the film; Reelstreets. However, I did not use any of the other websites as a source. Herewith are some comments on the locations I have discovered with reasonable confidence. They are given approximately in the scene order of the film. The map references are to the Dorling Kindersley Travel Guide for Paris, 2000 edition; but I would not expect later editions to change their main map pages. You may download a companion PDF to this web page; while the two are quite similar, the PDF has more details on why I think my identifications are correct, but the web version has more illustrations.

Except for Illustration 2, all photos courtesy Pat. (As, indeed, are most of the photos on this site.)

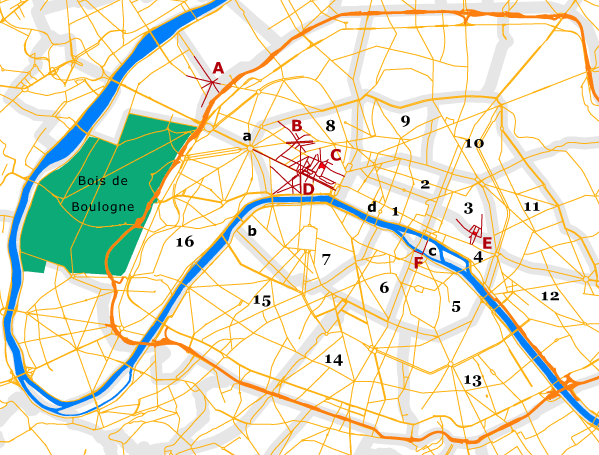

Map 1

Generalised map of central Paris.

Large numerals mark the arrondisements (with thick gray borders), blue

is the Seine, orange indicates the ring road

(Péripherique), gold indicates major roads, and dark red indicates roads

and places occuring in the film.

A: Bonnet house. B: Musée Jacquemart-André C: Elysée Palace.

D: Place François 1er and Rond Point des Champs Elysées. E: Musée

Carnavalet. F: final shot.

Major tourist sites: a: Arc de Triomphe, with the Avenue des Champs

Elysées extending SW. b: Eiffel Tower. c: Notre-Dame. d: Musée

du Louvre and the Tuileries Garden.

Data (unprojected) from the Open Street Map project

(www.openstreetmap.org); shapefiles courtesy www.geofabrik.de. NB: some

islands are missing from the data.

Audrey in her little car (added in Oct. 2018: according to someone on the IMDB [https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0060522/trivia?item=tr1330368], “Nicole’s car is a Autobianchi Bianchina Special Cabriolet”, introduced in 1960), listening to the art auction results. She drives past the east end of Notre-Dame cathedral, across the Pont de l’Archevêché connecting the Ile de la Cité to the Left Bank, and turns right onto the Quai de Montebello. Nearest Métro: Maubert Mutualité, Line 10. DK map 13, B4.

Cut to her arrival at the Bonnet mansion (actually around five kilometres away), driving through ironwork gates onto the dirt/gravel driveway and parking in front of a pair of curving stairs. Alas, the house is now gone—when we were looking for sites of the movie, we were right there without realizing it, not even suspecting that the house had been destroyed. It has been replaced by an ugly apartment building; perhaps the reason they chose this house for the film was that it had already been scheduled for demolition. The small brick building is still there, and is the “Octroi de Neuilly”, a collecting-booth for taxes on goods entering Paris (see Illustration 1); once upon a time this was the edge of Paris proper.

Illustration 1

Octroi de Neuilly, August

2009. My pot-bellied appearance is an optical illusion due to the

bunching up of my sweaters. Really.

https://www.neuillysurseine.fr/les-edifices-remarquables?BATI_NUM=31 states (at least I think it does—my French is pretty poor, even with the help of Google Translate) that the Octroi was built in 1909, architect Leopold Girauld, and is one of the few surviving Octroi buildings.

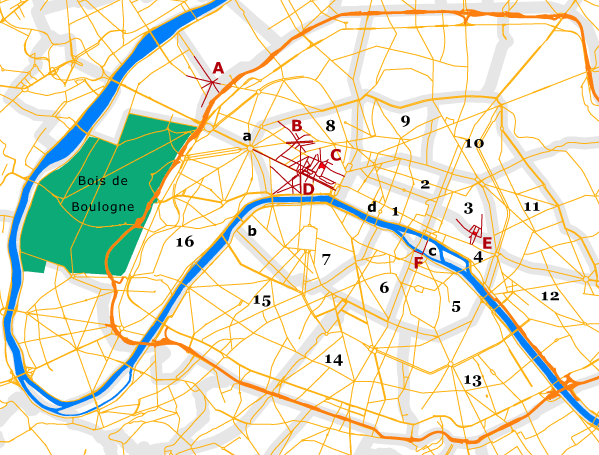

O’Toole later sends her home from the Ritz with instructions to the taxi driver to go to “38 Rue Parmentier” (not to be confused with Avenue Parmentier, in a different part of the city); the current apartment block does in fact bear that address (see Illustration 2). The Bonnet entrance gate appears to have been salvaged and moved a few metres down Rue Parmentier. The location is the intersection of Boulevard Bineau (D908), Rue de Villiers, Rue Louise Michel, Avenue de la Porte Villiers, Rue Parmentier, and Rue des Dames Augustines (labelled as the “Carrefour Bineau” on Google Maps). Nearest Métro: Porte de Champerret, Line 3. DK map 3, B1. (Louise Michel, Line 3, is a similar distance and a less awkward walk; not on the DK maps.)

Map 2

The neighbourhood of the Bonnet

house. The various colors for the roads are indicative of their relative

importance;

decreasing in stature from purple through orange, gold and pale green.

Dark brown marks subway stops.

The intersection of the six named streets is in front of 38 rue

Parmentier, and the house itself was

just above the P in ‘Porte de Villiers’. Data from www.openstreetmap.org; shapefiles courtesy

www.geofabrik.de.

Presumably the various streets, etc., with Parmentier in their title are named after the eighteenth-century’s Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, who should be much better-known. For information about an amazing man, see en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine-Augustin_Parmentier.

Illustration 2

The relocated Bonnet house

gate at the current 38 Rue Parmentier apartment building. From Google Street View.

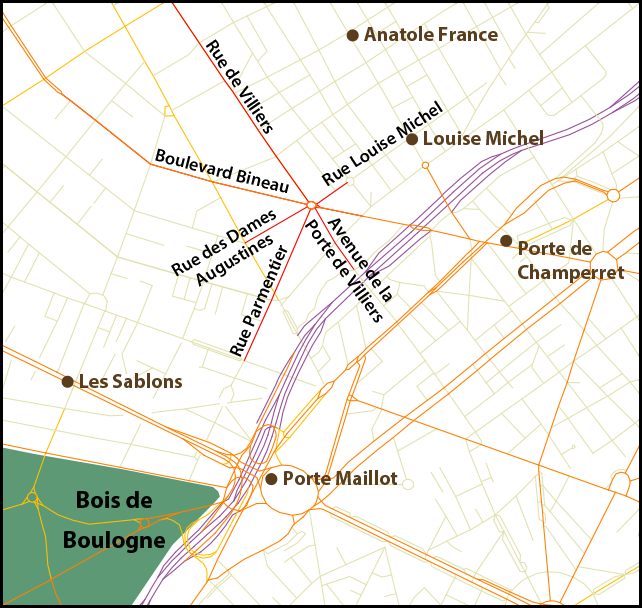

The “Cellini Venus” is transported to the imaginary “Kléber-Lafayette Museum”. This is the Musée Carnavalet, the museum of the history of Paris. For my plan of the museum, see Illustration 3. The true entrance to the museum is actually around the corner, on Rue de Sévigny; the gateway used in the movie is on Rue des Francs-Bourgeois. This gate opens into the Cour des Drapiers. The external walls (filthy at the time) and the frontages of the courtyard (only slightly less dirty) have at some time since received a much-needed cleaning, and the plantings have changed somewhat, but the building details match. This is a fabulous museum, with much more than just the history of the city. Nearest Métros: St. Paul, Line 1; Chemin Vert, Line 8. DK map 14, D3.

Illustration 3

Plan of the ground floor of

the Musée Carnavalet. The movie scenes are in the Cour des Drapiers. The

Cour de la Victoire is glimpsed through the arcade, but the two easterly

courtyards are never seen.

After the police carry the box containing the statue

to the entrance of the museum, there is a dissolve to our first view of

the interior of the museum, presumably later that day or perhaps within

a day or two. This supposed interior of the Kléber-Lafayette Museum is a

different location entirely: it is a reference to the gaudy Musée

Jacquemart-André, about four kilometers away from the

Carnavalet. Built by Henri Parent 1869–75, it is known for its

collection of Italian Renaissance paintings and frescoes; and French

18th century furniture, tapestries, ceramics and paintings. After

looking at numerous photos (and the museum’s website), it

is clear that they constructed

a very impressive set based closely upon the Jacquemart-André.

The movie staircase and the inlaid floors, and indeed the overall look of the ‘museum’,

are a tribute to production designer Alexandre Trauner.

Nearest Métro: St Philippe du Roule, Line 9.

DK Map 5,

A4.

Audrey drives her ‘burglar’ to the Ritz (“the what?!”). After zipping past the house, diagonally across to Rue Louise Michel, there is a short scene followed by a cut to the car zooming completely around a roundabout. This is the Place François 1er, formed by the intersection of Rue Bayard, Rue François 1er, and Rue Jean Goujon, just west of the Grand Palais. It is more than two kilometres away from the Bonnet house. Nearest Métro: Alma Marceau, Line 9. DK map 10, F1.

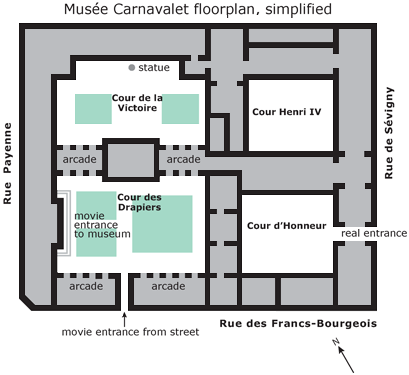

They arrive at the Hotel Ritz, on Place Vendôme. See Illustrations 4, 5 and 8. It has proved surprisingly difficult to pinpoint the location of the three-gate driveway where they pull up; there is no such drive-up entry to the hotel these days (short steel pylons block the building fronts of virtually the entire Place). The ironwork above the gate should be identifiable, with their kidney-shaped curlicues, but they do not quite match photos in a book I have seen about the Place Vendôme; the initials ‘AU’ (assuming they are to be read from the outside!) are visible in the central oval. Unfortunately, in Google’s street views many of the tops of arches are hidden by awnings, or covered by work in progress. The viewpoint appears to be correct for the left-hand portion of Ritz; perhaps things have simply changed out of recognition.

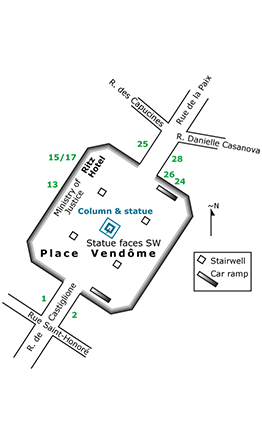

Illustration 4

Left: Plan of

Place Vendôme. The first section of the streets leaving the square

itself (until the cross-street) continue to have an address of Place

Vendôme, as indicated in green. Right: some of the ornate

ironwork seen on the second-floor balconies.

The houses on the Place date from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, designed by Hardouin-Mansart, and are (externally at least) surprisingly intact. Unfortunately, the atmosphere is rather spoiled by the parking and the large amount of through traffic. Not visible in the film are four pedestrian entrances to the below-ground parking, and two ramps leading down to the parking; perhaps the underground garage did not exist in the sixties. Aside from Ministry of Justice offices and the Ritz (both on the west side), the buildings are important offices (especially for insurance companies and banking) and the kind of grotesquely expensive shops that are common in this part of Paris (Dior, Chanel, Van Cleef and Arpels, etc.).

For comment about O’Toole’s room, see below (section 12). As for the Ritz bar, seen later on: the Ritz website has a fair amount of photos, but nothing resembles the movie setting. It seems likely that the hotel has gone through several changes of decor since the film; a search of contemporaneous photos of the Ritz should show whether the movie is accurate or these scenes are just studio shots. Nearest Métros: Opéra, Lines 3, 7, 8; Madeleine, Lines 8, 12, 14; Tuileries, Lines 7, 14; Pyramides, Lines 7, 14. DK map 6, D5 and 12, D1.

Illustration 5

View of the north-west

portion of the Place, with the Ministry of Justice on the left, the Ritz

Hotel on the right. Note the modern metal bollards controlling traffic and

parking.

The initial meeting between Audrey and ‘Davis Leland’ appears not to be in the Ritz (it is never stated where the dinner takes place); it has Art Nouveau touches which should make it identifiable (assuming it is not a set). On the website of John Williams, the composer for this film (www.johnwilliams.org/compositions/howtosteal.html), someone writes (it is apparently not Williams himself, as the section is in the third person) of a musical theme heard “first on piano at Maxim’s”, and states that the soundtrack of the movie contains a track entitled ‘At Maxim’s’. So someone thinks that this dining scene was filmed at Maxim’s, a very famous restaurant of Paris. In the 1989 book Inside Paris, author Joe Friedman decries the unfortunate “poor restoration and vulgar redecoration” inflicted upon the restaurant, so it is no longer possible to see it as it was in the film.

“Meet me at the corner of Avenue Gabriel [and] Avenue [de] Marigny” (see Illustrations 6 and 7). This is the south-western corner of the Elysée Palace grounds. The next few shots form O’Toole’s scouting trip, expressing his concerns about the excessive numbers of police. They proceed northwards along Avenue de Marigny, along the western wall of the palace grounds. The fancy iron and gold gate at the end of the road actually is the Ministry of the Interior, as Audrey says. Turning the corner, they pass the frontage of the Elysée Palace (“that’s where the President lives”) on Rue du Faubourg-St-Honoré—we saw fancy-pants guards emerge from the gateway and march down the street, just as in the movie. A couple of wooden guard posts are still on the sidewalk (see Illustration 8). In the cut to the next scene, to the Kléber-Lafayette Museum, they are instantly transported more than 2km. Nearest Métro: Champs Elysées Clemenceau, Lines 1, 13. DK map 5, B5.

Illustration 6

View of The Corner. August

2009, taken from the west side of Marigny looking toward the south-west

corner of the Palace.

Illustration 7

Closer view of the street

signs, August 2009. (It’s time to get a higher-resolution digital

camera!)

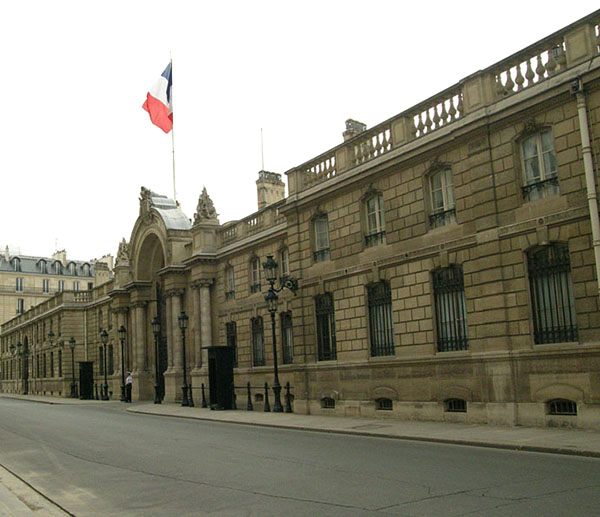

Illustration 8

The front of the Elysée

Palace, with wooden sentry boxes very much like those in the movie.

In the third interior scene at the museum, “casing the joint”, Audrey and Peter view the Venus from the top of the main staircase, then descend to examine the exhibit’s security. Cut to them walking arm-in-arm down the courtyard (the Cour des Drapiers of the Carnavalet), in a tracking shot which reveals virtually the entire north arcade and a glimpse of the east wall of the courtyard. There is then a cut intimating that they are nearby, walking towards a bench. The Eiffel Tower is visible in the background. I think this is the Rond Point des Champs-Elysées, although the flower beds are now much-changed, with the view towards the Tower along Avenue Montaigne. Nearest Métro: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lines 1, 9. DK map 5, A5.

The park where they encounter the boomerangs. This is a small park behind (west of) the Theatre Marigny, near the corner of Avenue Gabriel and Avenue de Marigny. The fountain is there, as is a yellow and white park building, with pierced balconies on the second floor, and rounded wings. The park is called Marigny Square (Carré Marigny). The fountain is the Fontaine du Cirque, possibly a reference to the original name of the building, Café du Cirque. The building is the high-end Restaurant Laurent. The orange-and-blue striped umbrella-thingy (it is over a carousel, though that is not immediately obvious) is not there in the current Google view, but it could easily be a seasonal feature, or simply have been removed in the past four decades. Nearest Métros: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lines 1, 9; Champs-Elysées Clemenceau, Lines 1, 13. DK map 5, A5.

Marigny Square (the stamp dealers market) is also used in the Stanley Donen film Charade (1962), starring Audrey Hepburn (!) and Cary Grant. It has a good view of the Café and the carousel (what is it with the French and carousels?), with glimpses of the nearby buildings.

The park where O’Toole practices the boomerang and announces he has a plan. The 40+ years which have passed since the making of the movie has made this very difficult to identify—trees have matured, or have been cut down and replaced; improvements have changed the road’s appearance. This location may be on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne near the Hippodrome de Longchamp (horse racing), and the bridge may be the Pont de Suresnes. The hill seen in the background when the camera pans to look directly across the Seine may be Mont Valerian, and the road they on which they leave may be the Allée du Bord de l’Eau (route D1). A lot of ‘may be’ but the area seems to have changed a great deal since 1966, and would need personal examination. Nearest Métros: Pont de Neuilly, Line 1; Boulogne/Pont de Saint-Cloud or Boulogne/Jean Jaurès, Line 10 (none of which are very close). There are several other stops on the east side of the Bois de Boulogne if you wish to have a stroll through the park (daylight hours only!). Not on the DK maps.

O’Toole’s room at the Ritz—“room 136”; assuming the Ritz uses standard room numbering practices, this would be on the ground floor or the second—British first—floor. This may be a set, as the view of the column outside seems to be an unconvincing rear projection. The viewpoint is correct for a room at the top level of the hotel, not the first, and if it is a set, they have done a good job, even including the angled ceiling one gets with a mansard roof. When he practices with the boomerang (were these a real toy of the mid-sixties?) he throws his leg over an appropriate wrought iron balcony, and when he looks directly down at the sidewalk (at the correct triple-headed lamp), it is a believable view, but from a room at the angle of a corner of the Place Vendôme—the last dormer window on the west side, and next to a nice oval window in the next part of the building, which is at a 45 degree angle from the west side. The view of the column shows the statue facing to the right; since the statue does indeed face south, this places the room on the correct side of the Place for the Ritz. It seems to me that the shot where he actually throws the boomerang places the room much closer to the middle of the west façade; that could be due to the mis-aligned rear projection, or using two different Ritz room locations.

Davis Leland leaves with the Venus. This is obviously not Roissy/Charles de Gaulle, as that only began construction in 1966. Much has changed at any major airport over the past 45 years; without seeing photos contemporaneous with the movie, it is difficult to tell, but I give the nod to Le Bourget (1919, and where Lindberg landed) over Orly (1932) because it is in more open territory and has fewer buildings. Another plus is the fact that Dassault (the makers of the Fanjet Falcon 20 aircraft depicted in the film—initially called the Dassault-Breguet Mystère 20—had a facility at Le Bourget, and the studio could have been borrowing/renting the plane for the scene at the airport. The control tower, lights, etc., have all changed, but no doubt an historian of French airports would be able to tell for certain. (added in Oct. 2018: according to wikipedia [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dassault_Falcon_20], “The Mystère 20 prototype was also featured in the 1966 comedy How to Steal a Million”. The prototype first flew in 1963. I believe that the “first of over 500 built” is not the same as the prototype, as production models are always held distinct from development builds.)

I cannot quite read the boast painted on the nose of the plane, but the series (which had models C through F at least) was apparently well-received, and used in many countries including the U.S. Crew of two, 10 passengers, and with a drop-down door to form the steps; there was indeed a washroom at the rear of the cabin. According to the journal FLIGHT International, dated 17 June 1965, the first of a 54-plane fleet for Pan American’s business jet division had arrived earlier that month, so the plane’s appearance in the movie would have seemed quite a modern touch. Federal Express began operation using several of these planes.

Audrey and Peter drive away from the house; there is then a cut to a long shot of the car driving along a road and crossing a river; as the camera pulls back, a view of Paris is revealed. The street is the Rue de la Cité, and they are going from Ile de la Cité to the left bank, across the Petit Pont (which is two bridges downstream from the Pont de l’Archevêché, seen in the film’s opening). The bridge next along is Pont St Michel, and the water is the left channel of the Seine as it divides around the islands. We can barely see the car turning right onto Quai St Michel and driving away under the credits. The view includes the Eiffel Tower and (I think) the two towers of St Sulpice on the left. It is tempting to think that this shot was filmed from the towers of Notre-Dame, but it is more likely that it was from the upper floors of the buildings of the Parvis.

And finally, the location of the studio shots is the Studios de Boulogne, founded in 1940 and home to many films (over 100 are listed on the Internet Movie Database), mostly French but with the occasional international film. Their website (www.sfp.fr/boulogne/film.php) includes this film in their 1965 productions (and Charade in 1962). The studio is only a few blocks south of the Bois de Boulogne, which perhaps lends credence to my suggestion for the location of the boomerang practising (see section 11).

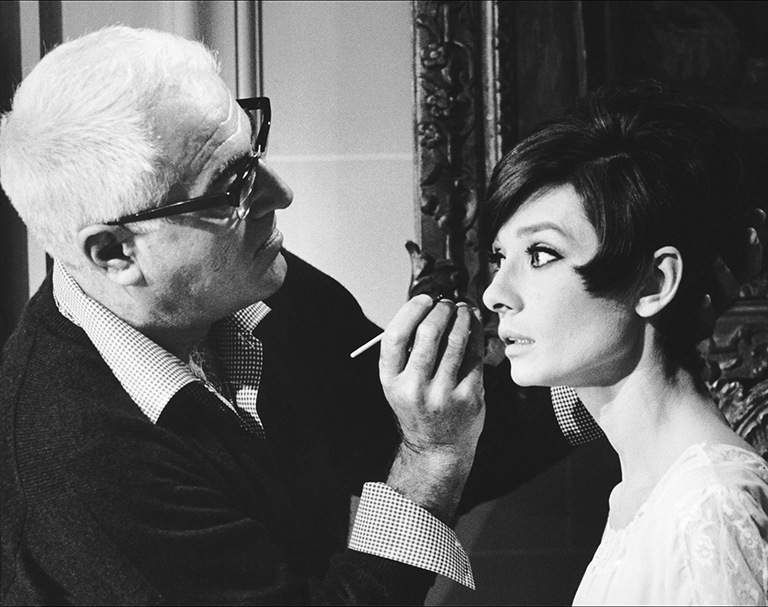

Illustration 9

From an on-line article “40 Rare Photos of Audrey Hepburn's Life”,

by Sam Escobar and Blake Bakkila, April 2019; see

https://www.goodhousekeeping.com/life/entertainment/g3641/audrey-hepburn-vintage-photos/?slide=22

The research for this document was largely done in August–November, 2009, using a variety of books, maps and websites, combined with a substantial amount of luck. A visit to Paris in late August 2009 was disappointing in terms of finding locations (I had not done enough homework), and stimulated a lot of effort after returning home to Toronto. I hope that we may return to Paris some day to check up on my more tentative suggestions.

I welcome input, especially for sections where you may disagree with my identification, or where I have been hesitant about deciding on a location. Please send e-mail to: million at-sign oh-no-not-again dot info. It would really be nice if someone in Paris could visit the Studios de Boulogne and make inquiries there about the movie locations and sets.

If you enjoy the process of tracking down Paris film locations, try Midnight In Paris, directed by Woody Allen, 2011. An excellent cast, superb photography, and missing the usual film-destroying ‘acting’ role played by Allen. Although I regard him as a vastly over-rated director, this is a lovely film, easily my favorite among his movies. Another exercise is the bizarre Paris When it Sizzles, starring Audrey Hepburn and William Holden, with a very minor appearance by Noël Coward and Tony Curtis.

©2012 by Duane Lakin-Thomas.

Illustration 10

The column of Place

Vendôme, with one of the three-headed lamps. The Ritz is on the far

side.